Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women are bucking the patriarchal, authoritarian stereotype of their community

Ultra-Orthodox women have become the primary breadwinners in their families. Menahem Kahana/AFP via Getty Images

Michal Raucher

Assistant Professor of Jewish Studies, Rutgers University

Ultra-Orthodox women have become the primary breadwinners in their families. Menahem Kahana/AFP via Getty ImagesUltra-Orthodox Jews have been in the news a lot lately, partly due to their reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic.

With a few exceptions, the stories present ultra-Orthodox Jews as a patriarchal community that is authoritarian and resistant to public health measures, even during a global pandemic. While this narrative has dominated coverage of this community for decades, it comes from a focus on ultra-Orthodox men.

Male community leaders are quoted in the media, and men are more visible among the crowds that are resisting and protesting lockdown measures. This reinforces both outside views of women in the community as subservient and internal attempts to silence and exclude women. But given the gender segregation in ultra-Orthodox communities, a complete picture of this society simply cannot be gleaned from men alone.

And when you look at ultra-Orthodox women, a picture of major societal change emerges. Women in the community are increasingly making reproductive decisions, working outside the home and resisting rabbis’ authority.

Reproductive decision-makers As a religious studies scholar who focuses on gender and Jews, I spent two years from 2009 to 2011 interviewing ultra-Orthodox women in Jerusalem about their reproductive experiences. What I heard then I see reflected in the dynamics in ultra-Orthodox communities in Israel today. We talked about their pregnancies – ultra-Orthodox women have about seven children on average – as well as their choice of contraception and prenatal tests.

What came out most prominently from our conversations and the many hours of observations I conducted in clinics and hospitals was that after several pregnancies, ultra-Orthodox women begin to take control over their reproductive decisions. This runs counter to what the rabbis expect of them. Rabbis expect ultra-Orthodox men and women to come to them for guidance on and permission for medical care. Knowing this, both male and female doctors might ask a woman who requests hormonal birth control, “Has your rabbi approved of this?”

This relationship cultivates mistrust among ultra-Orthodox women and leads them to distance themselves from both doctors and rabbis when it comes to reproductive care. However, this rejection of external authority over pregnancy and birth is supported by the ultra-Orthodox belief that pregnancy is a time when women embody divine authority. Women’s reproductive authority, then, is not completely countercultural; it’s embedded in ultra-Orthodox theology. Primary breadwinners while gender segregation has long been a feature of ultra-Orthodox ritual life, men and women now lead very different lives.

In Israel, ultra-Orthodox men spend most of their days in a Kollel, or religious institute, studying sacred Jewish texts. This task earns them a modest stipend from the government. While the community still valorizes poverty, ultra-Orthodox women have become the primary breadwinners. Over the past decade, they have increasingly attended college and graduate school in order to support their large families. In fact, they now enter the work force at a similar rate as their secular peers and are forging new careers in technology, music and politics, for example. New cultural representations Some recent TV shows depict this kind of nuanced understanding of gender and authority among ultra-Orthodox Jews.

Take the last season of the Netflix series “Shtisel,” for instance. In the TV show, Shira Levi, a young ultra-Orthodox woman from a Mizrahi background – which refers to Jews from the Middle East and North Africa – does scientific research. She enters into a relationship with one of the main Ashkenazi, or European Jewish, characters. Their ethnic differences end up being a bigger source of tension than Shira’s academic interests.

Another character, Tovi Shtisel, is a mother who works outside the home as a teacher. Despite objections from her husband, a Kollel student, she buys a car so she can get to work more efficiently.

And finally, Ruchami, who first appears as a teenager in season one, eagerly marries a Talmud scholar but struggles with a serious medical condition that makes pregnancy life-threatening. Despite her commitment to ultra-Orthodox life, she flouts rabbinic and medical rulings.

After her rabbi’s ruling that she should not have another child due to her medical risks, Ruchami decides to get pregnant without anybody’s knowledge.

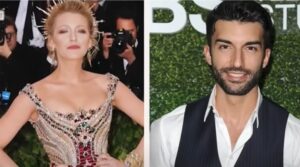

Ruchami Weiss, played by Shira Haas, in the Netflix series ‘Shtisel.’ Netflix These characters reflect my research that ultra-Orthodox women have a much different relationship to rabbinic authorities and pronouncements than men.

This is not just due to changing attitudes among women, however. Ultra-Orthodox society has been experiencing what some call a “crisis of authority” for years. Today there is a proliferation of new formal and informal leaders, leading to a diffusion of authority.

In addition to the many rabbis in ultra-Orthodox communities, their assistants or informal helpers, called askanim, operate pervasively. Ultra-Orthodox women also turn to theories that are repackaged in ultra-Orthodox language, like anti-vaccination campaigns. And finally, ultra-Orthodox Jews have created online groups that challenge the authority of leading rabbis.

Recognizing diversity The dominance of one narrative about ultra-Orthodox Jews’ reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic ignores other reasons why the virus spread so rapidly and devastatingly in these communities. Interviews with women would have revealed that poverty and cramped living spaces made social distancing almost impossible.

These conversations would have also revealed that although some consider Rabbi Chaim Kaneivsky, a 93-year-old ultra-Orthodox rabbi who has cultivated a significant following, to be the “king of COVID” for rejecting public health measures, there is no single rabbi whom all Israeli ultra-Orthodox Jews follow. In fact, many ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel have been following COVID-19 guidelines.

And furthermore, attention to women’s complicated experiences with the medical establishment would have highlighted the mistrust and doubt that permeates the ultra-Orthodox community’s relationship to public health measures. During a public health crisis, it is easy to demonize those who might not follow medical guidelines. But ultra-Orthodox Jews are diverse, and I believe understanding their complexity would enable better medical information and care to reach these populations.

Article republished with permission from TheConversation under Commons License.