After Hollywood thwarted Anna May Wong, the actress took matters into her own hands

Anna May Wong appears alongside Akim Tamiroff in a promotional poster for the 1939 film ‘King of Chinatown.’ LMPC/Getty Images - Licensed by Shutterstock to SyndicatedNews

By Shirley J. Lim

Professor of History, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York)

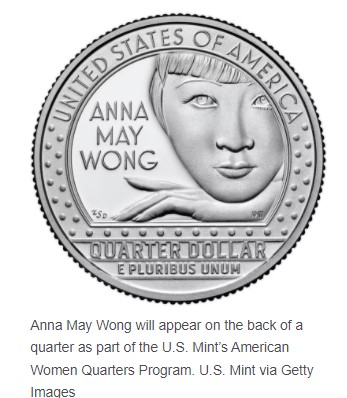

The U.S. Mint will, over the next four years, issue quarters featuring the likenesses of American women who contributed to “the development and history of our country.”

The first batch of the American Women Quarters Program, announced in January 2022, includes astronaut Sally Ride and poet Maya Angelou.

One name on the list might be less familiar to some Americans: Chinese American actress Anna May Wong.

As someone who has written a biography on Wong, I was delighted to provide the U.S. Mint with Wong’s backstory.

The subject of renewed attention in recent years, Wong is often referred to as a Hollywood star – in fact, the U.S. Treasury describes her as “the first Chinese American film star in Hollywood.” And she certainly did dazzle in her roles.

But to me, this characterization diminishes her chief accomplishment: her capacity for reinvention. Hollywood continually stymied her ambitions. And yet out of the ashes of rejection, she persevered, becoming an Australian vaudeville chanteuse, a British theatrical luminary, a B-film pulp diva and an American television celebrity.

A star is born

Born just outside of Los Angeles’ Chinatown in 1905, Wong grew up witnessing movies being made all around her. She dreamed of one day becoming a leading lady.

Cutting classes in order to beg directors for roles, Wong began her career as an extra in Alla Nazimova’s 1919 classic film about China’s Boxer Rebellion, “The Red Lantern.” In 1922, at the age of 17, Wong landed her first starring role in “The Toll of the Sea,” playing a character based on Madame Butterfly. Her performance was well received, and she went on to be cast as the Mongol slave in the 1924 hit film “The Thief of Bagdad.”

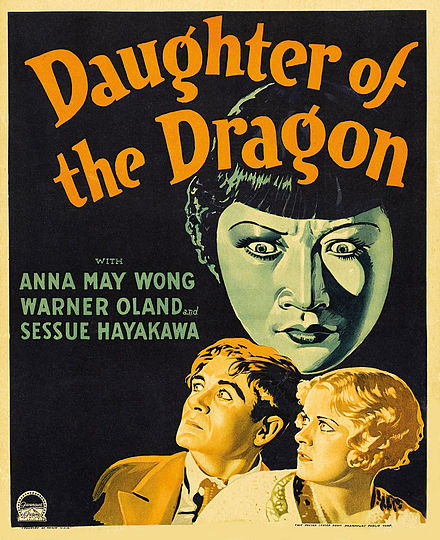

However, she quickly hit a wall in an era when it was common to cast white actors in yellowface – having them tape their eyes, wear makeup and assume exaggerated accents and gestures – to play Asian characters. (This practice would continue for decades: In 1961, director Blake Edwards egregiously cast Mickey Rooney as Mr. Yunioshi in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” and as recently as 2015, Emma Stone was controversially cast as a part-Chinese, part-Hawaiian character in “Aloha.”) Wong would go on to land roles playing unnamed minor characters in the 1927 film “Old San Francisco” and “Across to Singapore,” which premiered a year later. But anything outside of typecast roles seemed out of reach.

In some ways, her career mirrored that of the great Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa, who had forged a path for people of Asian Pacific descent in Hollywood. Hayakawa became a star through his headlining role in the 1915 Lasky-Famous Players film, “The Cheat.” However, as anti-Japanese sentiment increased in the U.S., his roles dried up. By 1922, he had left Hollywood.

European fame

Some actresses would have accepted their lot, grateful for the chance to simply appear in films.

Not Wong.

In 1928, fed up with a lack of opportunities in Hollywood, she packed her bags and sailed to Europe, where she became a global star.

From 1928 to 1934 she made a series of movies for Germany’s Universum-Film Aktiengeselleschaft, and found work with other leading studios such as France’s Gaumont and Associated Talking Pictures in the U.K. She impressed in her roles, attracting the attention of luminaries such as the German intellectual Walter Benjamin, British actor Laurence Olivier, German actress Marlene Dietrich and African American actor Paul Robeson. In Europe, Wong joined the ranks of African American artists such as Robeson, Josephine Baker and Langston Hughes, who, frustrated by segregation in the U.S., had left the country and found adulation in Europe.

When film work wasn’t forthcoming, Wong turned to vaudeville. In 1934, she embarked on a European tour, where she sang, danced and acted before enthralled audiences in cities large and small, from Madrid to Göteborg, Sweden.

Wong’s revue showcased her chameleonlike powers to transform herself. In Göteborg, for example, she performed eight numbers that included the Chinese folk song “Jasmine Flower” and the contemporary French hit “Parlez-moi d’Amour.” Inhabiting a variety of roles and races, she seamlessly shifted from speaking Chinese to French, from portraying a folk singer to appearing as a tuxedo-clad nightclub siren.

Wong decides to do it on her own

What I love about Wong is that even as Hollywood thwarted her time and again, she continued creating her own opportunities.

Though she spent years in Europe, Wong continued to audition for American roles.

In 1937, she tried out for the leading role in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s “The Good Earth.” After she was rejected, she decided that if she couldn’t star in a movie, she would simply make one of her own.

She took her one and only trip to China, documenting the experience. Her charming short film showed numerous activities, including female impersonators teaching Wong how to enact Chinese female roles, a trip to the Western Hills, and a visit to the family’s ancestral village. At a time when the number of prominent female directors in Hollywood could be counted on one hand, it was a remarkable feat.

Two decades later, the film would air on ABC. By that time, Wong had established herself as a TV star by playing a gallery owner-cum-detective who traveled the globe solving crimes in “The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong.” It was the first television series to feature an Asian Pacific American lead.

By the time Wong died on February 3, 1961, she had left a legacy of more than 50 films, numerous Broadway and vaudeville shows, and a television series. Equally important is how she became a global celebrity despite being shut out from Hollywood’s A-list leading roles.

It’s a story of tenacity and determination that can inspire all who wacnt to see images of people of color reflected back to them on screen.

Republished with permission from THE CONVERSATION under Creative Commons License.