Before Shark Week and ‘Jaws,’ World War II spawned America’s shark obsession

A painting for the U.S. Army’s Stars and Stripes newspaper shows a downed pilot fending off sharks with a knife. Ed Vebell/Getty Images

Janet M. Davis

University Distinguished Teaching Professor of American Studies,

The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

Every summer on the Discovery Channel, “Shark Week” inundates its eager audiences with spectacular documentary footage of sharks hunting, feeding and leaping.

Debuting in 1988, the television event was an instant hit. Its financial success wildly exceeded the expectations of its creators, who had been inspired by the profitability of the 1975 blockbuster film “Jaws,” the first movie to earn US$100 million at the box office.

Thirty-three years later, the enduring popularity of the longest-running programming event in cable TV history is a testament to a nation terrified and fascinated by sharks.

Journalists and scholars often credit “Jaws” as the source of America’s obsession with sharks.

Yet as a historian analyzing human and shark entanglements across the centuries, I argue that the temporal depths of “sharkmania” run much deeper.

World War II played a pivotal role in fomenting the nation’s obsession with sharks. The monumental wartime mobilization of millions of people placed more Americans into contact with sharks than at any prior time in history, spreading seeds of intrigue and fear toward the marine predators.

America on the move

Before World War II, travel across state and county lines was uncommon. But during the war, the nation was on the move.

Out of a population of 132.2 million people, per the 1940 U.S. Census, 16 million Americans served in the armed forces, many of whom fought in the Pacific. Meanwhile, 15 million civilians crossed county lines to work in the defense industries, many of which were in coastal cities, such as Mobile, Alabama; Galveston, Texas; Los Angeles; and Honolulu.

Local newspapers across the country transfixed civilians and servicemen alike with frequent stories of bombed ships and aircraft in the open ocean. Journalists consistently described imperiled servicemen who were rescued or dying in “shark-infested waters.”

Whether sharks were visibly present or not, these news articles magnified a growing cultural anxiety of ubiquitous monsters lurking and poised to kill.

The naval officer and marine scientist H. David Baldridge reported that fear of sharks was a leading cause of poor morale among servicemen in the Pacific theater. General George Kenney enthusiastically supported the adoption of the P-38 fighter plane in the Pacific because its twin engines and long range diminished the chances of a single-engine aircraft failure or an empty fuel tank: “You look down from the cockpit and you can see schools of sharks swimming around. They never look healthy to a man flying over them.”

‘Hold tight and hang on’

American servicemen became so squeamish about the specter of being eaten during long oceanic campaigns that U.S. Army and Navy intelligence operations engaged in a publicity campaign to combat fear of sharks.

Published in 1942, “Castaway’s Baedeker to the South Seas” was a “travel” survival guide, of sorts, for servicemen stranded on Pacific islands. The book emphasized the critical importance of conquering such “bogies of the imagination” as “If you are forced down at sea, a shark is sure to amputate your leg.”

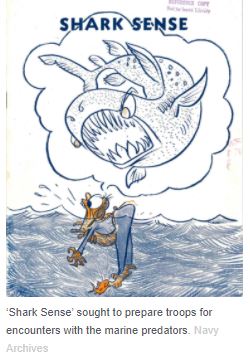

Similarly, the Navy’s 1944 pamphlet titled “Shark Sense” advised wounded servicemen stranded at sea to “staunch the flow of blood as soon as you disengage the parachute” to thwart hungry sharks. The pamphlet helpfully noted that hitting an aggressive shark on the nose might stop an attack, as would grabbing a ride on the pectoral fin: “Hold tight and hang on as long as you can without drowning yourself.”

The Department of the Navy also worked with the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency, to develop a shark repellent

Office of Strategic Services executive assistant and future chef Julia Child worked on the project, which tested various recipes of clove oil, horse urine, nicotine, rotting shark muscle and asparagus in hopes of preventing shark attacks.

The project culminated in 1945, when the Navy introduced “Shark Chaser,” a pink pill of copper acetate that produced a black inky dye when released in the water – the idea being that it would obscure a serviceman from sharks. .

Nonetheless, the U.S. military’s morale-boosting campaign was unable to vanquish the glaring reality of wartime carnage at sea. Military media correctly observed that sharks rarely attack healthy swimmers. Indeed, malaria and other infectious diseases took a far greater toll on U.S. servicemen than sharks.

But the same publications also acknowledged that an injured person was vulnerable in the water. With the frequent bombing of airplanes and ships during World War II, thousands of injured and dying servicemen bobbed helplessly in the ocean.

One of the worst wartime disasters at sea occurred on July 30, 1945, when pelagic sharks swarmed the site of the shipwrecked USS Indianapolis. The heavy cruiser, which had just successfully delivered the components of the Hiroshima atomic bomb to Tinian Island in a top-secret mission, was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. Out of a crew of 1,196 men, 300 died immediately in the blast, and the rest landed in the water. As they struggled to stay afloat, men watched in terror as sharks feasted on their dead and wounded shipmates.

Only 316 men survived the five days in the open ocean.

Jaws’ has an eager audience

World War II veterans possessed searing lifelong memories of sharks – either from direct experience or from the shark stories of others. This made them an especially receptive audience for Peter Benchley’s taut shark-centered thriller “Jaws,” which he published in 1974.

Don Plotz, a Navy sailor, immediately wrote to Benchley: “I couldn’t put it down until I had finished it. For I have rather a personal interest in sharks.”

In vivid detail, Plotz recounted his experiences on a search and rescue mission in the Bahamas, where a hurricane had sunk the USS Warrington on Sept. 13, 1944. Of the original crew of 321, only 73 survived.

“We picked up two survivors who had been in the water twenty-four hours, and fighting off sharks,” Plotz wrote. “Then we spent all day picking up the carcasses of those we could find, identifying them and burying. Sometime only rib cages … an arm or leg or a hip. Sharks were all around the ship.”

Benchley’s novel paid little attention to World War II, but the war anchored one of the movie’s most memorable moments. In the haunting, penultimate scene, one of the shark hunters, Quint, quietly reveals that he is a survivor of the USS Indianapolis disaster.

“Sometimes the sharks look right into your eyes,” he says. “You know the thing about a shark, he’s got lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes. He comes at you, he doesn’t seem to be living until he bites you.”

The power of Quint’s soliloquy drew upon the collective memory of the most massive wartime mobilization in American history. The oceanic reach of World War II placed greater numbers of people into contact with sharks under the dire circumstances of war. Veterans bore intimate witness to the inevitable violence of battle, compounded by the trauma of seeing sharks circle and feed opportunistically on their dead and dying comrades.

Their horrifying experiences played a pivotal role in creating an enduring cultural figure: the shark as a mindless, spectral terror that can strike at any moment, a haunting artifact of World War II that primed Americans for the era of “Jaws” and “Shark Week.”

This article is republished with permission from TheConversation under a commons license.