Underneath all the makeup, who was the real Tammy Faye?

John Wigger

Professor of History, University of Missouri-Columbia

What is it about televangelists Tammy Faye and Jim Bakker that continues to fascinate nearly 35 years after the fall of their evangelical empire?

Jim Bakker still makes headlines selling survival food and miracle cures from his television compound near Branson, Missouri. While Tammy Faye died in 2007, a new biopic about her, “The Eyes of Tammy Faye,” stars Jessica Chastain as Tammy.

Jim and Tammy rose to fame in the 1970s and 1980s as the married hosts of a Christian television talk show called “The PTL Club.” The show was broadcast live, with a studio audience, five days a week, with little scripting. It was reality television before there was a name for it, and the show, at its peak, was beamed via satellite into 14 million American homes.

The format of “The PTL Club” was largely Jim’s invention, but it was Tammy whom people came to love. For my book “PTL: The Rise and Fall of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Evangelical Empire,” I spoke with dozens of former PTL staffers. They all remember Tammy in pretty much the same way: candid, spontaneous and charismatic.

She said exactly what was on her mind, no matter how inappropriate. Viewers watched just to see what she would say next. And while evangelicals are often portrayed as intolerant fundamentalists, Tammy represented a different side of the faith.

Getting started

Born in 1942, Tammy LaValley grew up in a house without indoor plumbing in International Falls, Minnesota, the oldest of eight children. She attended Pentecostal churches with her mother and aunt and never wore lipstick or went to the movies until she was married.

In 1960, Tammy left home to attend North Central Bible College in Minneapolis. There she met Jim Bakker, who had arrived the year before.

On their third date, Jim proposed. They married on April 1, 1961, bought a used Plymouth Valiant and set off to become Pentecostal healing evangelists, traveling a circuit throughout the Bible Belt.

Looking to broaden their appeal, they created a puppet show for children who attended their meetings. Tammy was brilliant with her puppets, giving each a voice and personality. She used them to say things she could not otherwise express, sometimes continuing earlier arguments she’d had with Jim in front of the kids and parents who gathered for the show.

“I guess it was therapy for me,” she later wrote in her autobiography.

PTL shoots into orbit

The puppet show brought them to the attention of Pat Robertson, a recent seminary graduate who had just launched a tiny Christian television station in Portsmouth, Virginia.

“The Jim and Tammy Show” – a children’s variety show that featured Tammy’s puppets – soon became the station’s most popular program.

In 1974, the Bakkers moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, to start the PTL television network with a half-dozen employees in a former furniture store. Four years later, PTL – an abbreviation that originally stood for “Praise the Lord,” but sometimes morphed into “People That Love” – started its own satellite network. Only HBO and Ted Turner’s WTBS station in Atlanta were quicker to make the jump to satellite than PTL. ESPN wouldn’t launch until a year later.

Thanks to the satellite network’s national reach, donations to the ministry poured in. Jim and Tammy quickly became television stars.

Apart from hosting the flagship talk show with Jim, Tammy at times had her own television shows aimed at women, the last of which was called “Tammy’s House Party,” in which she cooked and talked decorating, fashion and makeup with guests. She wanted her shows to be fun and less overtly religious than Jim’s. (She once did an entire show on a merry-go-round, and one of the show’s cast members threw up inside the dog costume he was wearing.)

For a dozen years Tammy threw herself into PTL’s ministry. But performing on television was never what she really wanted. She was smart but lacked confidence, often hiding her insecurities with ditzy self-deprecation. She never, she wrote, thought she was “pretty enough, thin enough or talented enough.”

Instead, as Tammy wrote in her second autobiography, the “happiest time” in her life was when she got to spend time with her two children, Tammy Sue and Jamie, and just “be a Mom.”

There was something in Tammy that resisted Jim’s relentless marketing of their faith. When promoting her first autobiography on an episode of “The PTL Club,” Tammy said that if she could not be herself, she would be Sophia Loren or Dolly Parton.

Jim jumped in and suggested that she should have said Kathryn Kuhlman, the famous healing evangelist, or “someone spiritual.”

Tammy disagreed.

Perils of prosperity

Coinciding with their rise to fame, the Bakkers embraced the prosperity gospel, which taught believers to expect the best of everything. In the era of post-World War II affluence, the good life and the godly life merged.

The message fit the 1980s perfectly. Many evangelicals might not have agreed with Gordon Gecko, the fictional character portrayed by Michael Douglas in the 1987 film “Wall Street,” that “Greed is good,” but they generally had little patience for the notion that restraint, let alone poverty, was any better.

“God wants you to be happy, God wants you to be rich, God wants you to prosper,” Jim wrote in his 1980 book, “Eight Keys to Success.” The couple used PTL money to buy a 10,000-square-foot home near Charlotte, a Florida beach condo and vacation homes in Palm Springs and Palm Desert, California, along with one in Gatlinburg, Tennessee.

Even so, the money was never central to Tammy’s identity. Yes, she was legendary for her love of shopping. But she was just as happy to scrounge through bargain bins as buy from upscale stores.

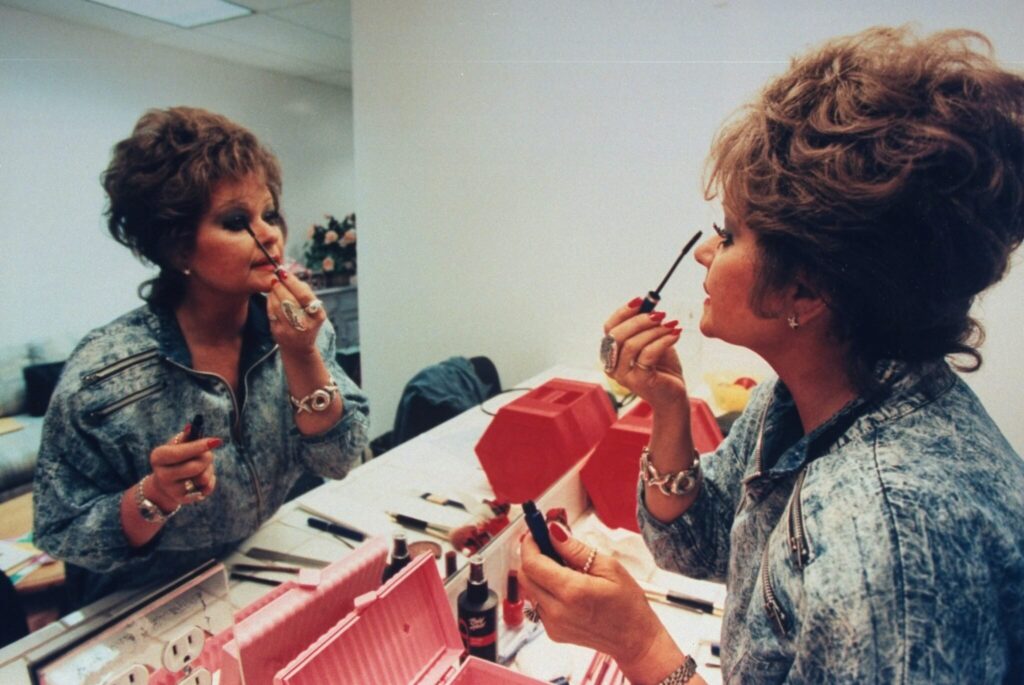

By this time, Tammy had dramatically transformed her image, adding the thick makeup for which she became famous.

“Not by any stretch of the imagination does she look like a preacher’s wife,” wrote a reporter for a Charlotte newspaper. She more resembled “a country music singer or a nightclub entertainer.”

PTL staffers that I interviewed said that they could tell what sort of mood she was in as soon as she walked in the door. If her makeup was relatively light and she was wearing only her natural hair, it would be a good day. If her makeup was thick and she had on a Parton-style wig, they were in for trouble.

She hid behind her makeup much in the way she had hidden behind her puppets.

As Jim became obsessed with building Heritage USA, PTL’s 2,300-acre theme park, their marriage fell apart. Tammy was already having an affair when they took their show on location in Hawaii for a month in late 1980. There, Tammy told Jim she was moving out and wanted a divorce.

“That was a miserable, miserable time,” Don Hardister, PTL’s longtime head of security, told me in an interview for my book.

Jim and Tammy reconciled, but enduring the whirlwind that was PTL continued to take its toll. By 1987 Tammy was addicted to a range of prescription drugs, including Valium.

Two years later Jim was sentenced to 45 years in federal prison for wire and mail fraud. They divorced in 1992.

Tammy perseveres

After PTL, Tammy branched out in ways that brought her new fans. She had been one of the first public figures in the 1980s to reach out to gay men who were dying of AIDS, at a time when there was a great deal of fear about the disease.

In 1996 she co-starred with the openly gay actor Jim J. Bullock in “The Jim J. and Tammy Faye Show,” a nationally syndicated daytime talk show.

Tammy was “all about acceptance,” Bullock told me. She left the show in 1996 when she was diagnosed with colon cancer. By then she had become, as Entertainment Weekly put it, the “Judy Garland of televangelism.”

The Bakkers represent two sides of the evangelical coin. Jim had a better sense of what would sell in the cultural moment, seizing upon the prosperity gospel during the go-go 1980s and then tapping into end-times survivalism in the wake of 9/11.

But Tammy had a better feel for what would endure, a stronger sense of how to keep faith relevant and connected to people over the long haul. Her vulnerability and compassion give her a timelessness not tied to the politics of the moment. Her faith was more holistic, and less a vehicle for power.

When asked what she wanted to be remembered for shortly before she died, Tammy replied, “my eyelashes,” and then, “my walk with the Lord.”

She was right about both.

Article republished with permission from The Conversation under a commons license.

Afrikaans

Afrikaans Albanian

Albanian Amharic

Amharic Arabic

Arabic Armenian

Armenian Azerbaijani

Azerbaijani Basque

Basque Belarusian

Belarusian Bengali

Bengali Bosnian

Bosnian Bulgarian

Bulgarian Catalan

Catalan Cebuano

Cebuano Chinese (Simplified)

Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Traditional)

Chinese (Traditional) Corsican

Corsican Croatian

Croatian Czech

Czech Danish

Danish Dutch

Dutch Esperanto

Esperanto Estonian

Estonian Filipino

Filipino Finnish

Finnish French

French Frisian

Frisian Galician

Galician Georgian

Georgian German

German Greek

Greek Gujarati

Gujarati Haitian Creole

Haitian Creole Hausa

Hausa Hawaiian

Hawaiian Hebrew

Hebrew Hindi

Hindi Hmong

Hmong Hungarian

Hungarian Icelandic

Icelandic Indonesian

Indonesian Irish

Irish Italian

Italian Japanese

Japanese Javanese

Javanese Kannada

Kannada Kazakh

Kazakh Khmer

Khmer Korean

Korean Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz Lao

Lao Latin

Latin Latvian

Latvian Lithuanian

Lithuanian Luxembourgish

Luxembourgish Macedonian

Macedonian Malagasy

Malagasy Malay

Malay Malayalam

Malayalam Maltese

Maltese Maori

Maori Marathi

Marathi Mongolian

Mongolian Myanmar (Burmese)

Myanmar (Burmese) Nepali

Nepali Norwegian

Norwegian Pashto

Pashto Persian

Persian Polish

Polish Portuguese

Portuguese Punjabi

Punjabi Romanian

Romanian Russian

Russian Samoan

Samoan Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic Serbian

Serbian Sesotho

Sesotho Shona

Shona Sindhi

Sindhi Sinhala

Sinhala Slovak

Slovak Slovenian

Slovenian Somali

Somali Spanish

Spanish Sundanese

Sundanese Swahili

Swahili Swedish

Swedish Tajik

Tajik Tamil

Tamil Telugu

Telugu Thai

Thai Turkish

Turkish Ukrainian

Ukrainian Urdu

Urdu Uzbek

Uzbek Vietnamese

Vietnamese Welsh

Welsh Yiddish

Yiddish Yoruba

Yoruba Zulu

Zulu