This Hanukkah, learn about the holiday’s forgotten heroes: Women

A Jewish woman lights a candle for the festival of Hanukkah at the Western Wall Plaza in Jerusalem. (Marco Longari/AFP via Getty Images)

Alan Avery-Peck

Kraft-Hiatt Professor in Judaic Studies, College of the Holy Cross

The eight-day Jewish festival of Hanukkah commemorates ancient Jews’ victory over the powerful Seleucid empire, which ruled much of the Middle East from the third century B.C. to the first century A.D.

On the surface, it’s a story of male heroism. A ragtag rebel force led by a rural priest and his five sons, called the Maccabees, freed the Jews from oppressive rulers. Hanukkah, which means “rededication” in Hebrew, celebrates the Maccabees’ victory, which allowed the Jews to rededicate their temple in Jerusalem, the center of ancient Jewish worship.

But as a professor of Jewish history, I believe that seeing Hanukkah this way misses the inspiring women who were prominent in the earliest tellings of the story.

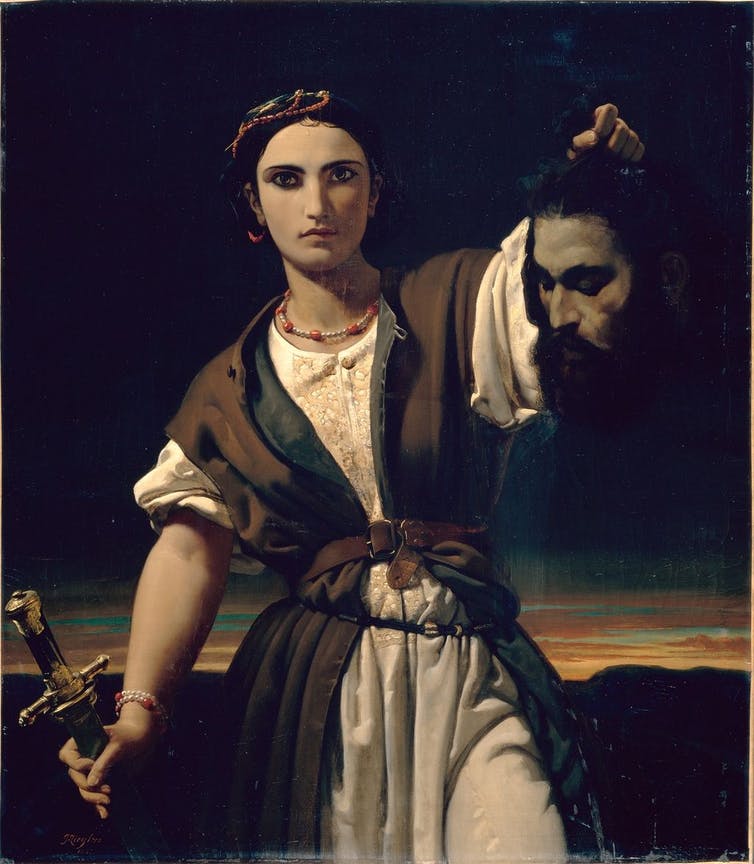

The bravery of a young widow named Judith is at the heart of an ancient book that bears her name. The heroism of a second woman, an unnamed mother of seven sons, appears in a book known as 2 Maccabees.

Saving Jerusalem

These books are not included in the Hebrew scriptures, but appear in other collections of religious texts known as the Septuagint and the Apocrypha.

According to these texts, Judith was a young Israelite widow in a town called Bethulia, strategically situated on a mountain pass into Jerusalem. To besiege Jerusalem, the Seleucid army first needed to capture Bethulia.

Facing such a formidable enemy, the townsfolk were terrified. Unless God immediately intervened, they decided, they would simply surrender. Enslavement was preferable to certain death.

But Judith scolded the local leaders for testing God, and was brave enough to take matters into her own hands. Removing her widow’s clothing, she entered the enemy camp. She beguiled the Seleucid general, Holofernes, with her beauty, and promised to give her people over to him. Hoping to seduce her, Holofernes prepared a feast. By the time his entourage left him alone with Judith, he was drunk and asleep.

Now she carried out her plan: cutting off his head and escaping back to Bethulia. The following morning, the discovery of Holofernes’ headless body left the Seleucid army trembling with fear. Soldiers fled by every available path as Bethulia’s Jews, recovering their courage, rushed in and slaughtered them. Judith’s bravery saved her town and, with it, Jerusalem.

A family’s sacrifice

The book of 2 Maccabees, Chapter 7, meanwhile, relates the story of an unnamed Jewish mother and her seven sons, who were seized by the Seleucids.

Emperor Antiochus commanded that they eat pork, which is forbidden by the Torah, to show their obedience to him. One at a time, the sons refused. An enraged Antiochus subjected them to unspeakable torture. Each son withstood the ordeal and is portrayed as a model of bravery. Resurrection awaits those who die in the service of God, they proclaimed, while for Antiochus and his followers, only death and divine punishment lay ahead.

Throughout these ordeals, their mother encouraged her sons to accept their suffering. “She reinforced her woman’s reasoning with a man’s courage,” as 2 Maccabees relates, and admonished her sons to remember their coming reward from God.

Having killed the first six brothers, Antiochus promised the youngest a fortune if only he would reject his faith. His mother told the boy, “Accept death, so that in God’s mercy I may get you back again along with your brothers.” The story in 2 Maccabees ends with the simple statement that, after her sons’ deaths, the mother also died.

Later retellings give the mother a name. Most commonly, she is called Hannah, based on a detail in the biblical book of 1 Samuel. In this section, called the “prayer of Hannah,” the prophet Samuel’s mother refers to herself as having borne seven children.

Working with God

Jewish educator and author Erica Brown has emphasized a lesson we should learn from the story of Judith, one that emerges from 2 Maccabees as well. “Just like the Hanukkah story generally, the message of these texts is that it’s not always the likely candidates who save the day,” she writes. “Sometimes salvation comes when you least expect it, from those who are least likely to deliver it.”

Three hundred years after the Maccabean revolt, Judaism’s earliest rabbis stressed a similar message. Adding a new focus to Hanukkah, they spoke of a divine miracle that occurred when the ancient Jews took back the Temple and wanted to relight the holy “eternal flame” inside. They found just one small vessel of oil, sufficient to light the flame for only one day – but it lasted eight days, giving them time to produce a new supply.

As the influential rabbi David Hartman pointed out, the Hanukkah story celebrates “our people’s strength to live without guarantees of success.” Some ordinary person, he points out, took the initiative to rekindle the eternal flame, despite how futile doing so may have seemed.

Ever since, Judaism has increasingly focused on the interaction of the human and the divine. The Hanukkah story teaches listeners that they all must play a part to repair a hurting world. Not everyone needs to be a Judith or Hannah; but, like them, we humans can’t wait for God to take care of it.

In synagogues, one of the readings for the week during Hanukkah is from the prophet Zechariah, who proclaimed, “Not by might, nor by power, but by my spirit, says the Lord of hosts.” These words succinctly capture the meaning of Hanukkah and express what Jews might think about while lighting the Hanukkah candles: our responsibility to act in the spirit of God to create the miracles the world needs to become a place of beauty, equity and freedom.

Article republished with permission from TheConversation under commons license.